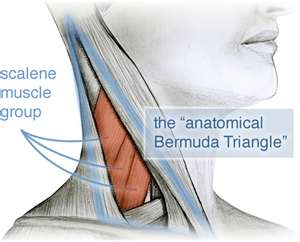

The Scalenes are an important neck muscle comprised of three parts, the anterior, the middle, and the posterior. The anterior and the middle will be the subject of this post because the posterior is mostly involved as a synergist for the upper trapezius. The brachial plexus passes through an opening between the anterior and middle scalenes, making it subject to dysfunction if the scalenes are hypertonic.  The scalenes are also accessory muscles of respiration and can cause breathing imbalances if one is a chest breather. The scalenes are also involved in the kinetic chain of the arm as well as the front line and lateral line. We will examine all of these relationships to reveal just how dynamic these muscles truly are.

The scalenes are also accessory muscles of respiration and can cause breathing imbalances if one is a chest breather. The scalenes are also involved in the kinetic chain of the arm as well as the front line and lateral line. We will examine all of these relationships to reveal just how dynamic these muscles truly are.

In cervical dysfunction the scalenes can be either facilitated or inhibited. If the sternocleidomastoid muscle is inhibited, the scalenes may compensate to stabilize neck flexion. In the case of whiplash, the scalenes may become inhibited by facilitated neck extensors. I find it very important to release the scalenes indirectly by stabilizing the first and second ribs while performing a myofascial stretch. I have found that working directly on the scalenes can cause them to rebound and tighten up even further. To strengthen the scalenes, resist at the forehead while nodding towards the ipsilateral shoulder. The scalenes also ipsilaterally flex the neck, and therefore can become inhibited by either the ipsilateral or contralateral upper trapezius. The scalenes produce ipsilateral rotation of the cervical spine, and can become facilitated by an inhibited contralateral sternocleidomastoid or an ipsilateral longus colli.

In cervical dysfunction the scalenes can be either facilitated or inhibited. If the sternocleidomastoid muscle is inhibited, the scalenes may compensate to stabilize neck flexion. In the case of whiplash, the scalenes may become inhibited by facilitated neck extensors. I find it very important to release the scalenes indirectly by stabilizing the first and second ribs while performing a myofascial stretch. I have found that working directly on the scalenes can cause them to rebound and tighten up even further. To strengthen the scalenes, resist at the forehead while nodding towards the ipsilateral shoulder. The scalenes also ipsilaterally flex the neck, and therefore can become inhibited by either the ipsilateral or contralateral upper trapezius. The scalenes produce ipsilateral rotation of the cervical spine, and can become facilitated by an inhibited contralateral sternocleidomastoid or an ipsilateral longus colli.

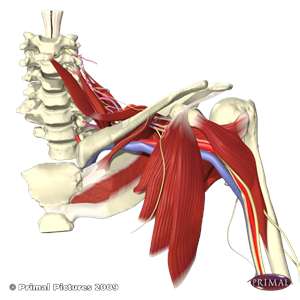

Because the brachial plexus passes through an opening between the anterior and middle scalenes, hypertonicity, whether caused by facilitation or inhibition, must be addressed. The extra pressure on the brachial plexus caused by hypertonic scalenes can result in Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Symptoms include numbness and tingling in the arms and hands, as well as loss of strength in both the arms and hands. I have found the scalenes to be compensating for 13 different functions in the arm line with someone who had TOS. Reestablishing the proper relationship between the scalenes and these 13 different functions was crucial in the resolution of the TOS.

Because the brachial plexus passes through an opening between the anterior and middle scalenes, hypertonicity, whether caused by facilitation or inhibition, must be addressed. The extra pressure on the brachial plexus caused by hypertonic scalenes can result in Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Symptoms include numbness and tingling in the arms and hands, as well as loss of strength in both the arms and hands. I have found the scalenes to be compensating for 13 different functions in the arm line with someone who had TOS. Reestablishing the proper relationship between the scalenes and these 13 different functions was crucial in the resolution of the TOS.

The scalenes are an important part of the front line kinetic chain. It is not unusual for the scalenes to be facilitated for an inhibited ipsilateral psoas and adductors. They may also be facilitated for an inhibited contralateral TFL and adductors. Even dysfunction of the extensor hallucis longus can be compensated for by the ipsilateral scalenes.

The scalenes are an important part of the front line kinetic chain. It is not unusual for the scalenes to be facilitated for an inhibited ipsilateral psoas and adductors. They may also be facilitated for an inhibited contralateral TFL and adductors. Even dysfunction of the extensor hallucis longus can be compensated for by the ipsilateral scalenes. In the lateral line, the scalenes oftentimes become facilitated in combination with the peroneals in cases of over pronation or ankle sprains. The most likely inhibited muscle in this scenario is the TFL. The scalenes can also be dynamically involved with the obliques and the quadratus lumborum.

In the lateral line, the scalenes oftentimes become facilitated in combination with the peroneals in cases of over pronation or ankle sprains. The most likely inhibited muscle in this scenario is the TFL. The scalenes can also be dynamically involved with the obliques and the quadratus lumborum.

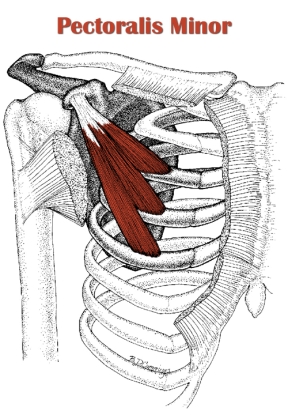

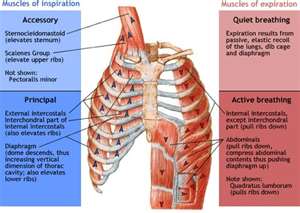

The scalenes are also accessory muscles of respiration. They elevate the first and second ribs, and in chest breathers, they can become,along with the pectoralis minor, dominant muscles of respiration. In this situation they can become facilitated for inhibition of the muscles that depress the rib cage, such as the quadratus lumborum and the obliques. Resolution of these dynamic muscular relationships along with restoration of proper breathing patterns can go a long way to resolving this issue.

The scalenes are also accessory muscles of respiration. They elevate the first and second ribs, and in chest breathers, they can become,along with the pectoralis minor, dominant muscles of respiration. In this situation they can become facilitated for inhibition of the muscles that depress the rib cage, such as the quadratus lumborum and the obliques. Resolution of these dynamic muscular relationships along with restoration of proper breathing patterns can go a long way to resolving this issue.

The scalenes are important to consider in cervical dysfunction, Thoracic Outlet Syndrome, problems with the arms and hands, dysfunction of the muscles of the front line, dysfunction of the muscles of the lateral line, and improper breathing patterns. Remember to treat these muscles with respect and they will reward you with outstanding therapeutic outcomes.